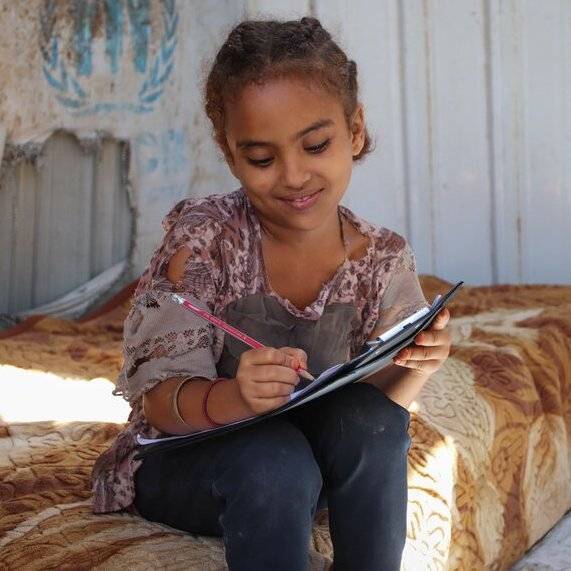

All Images: Matt Inwood

Goal 2: Zero Hunger

Seven Days of Hunger To Help Refugees

To celebrate the strength of the 82.4 million refugees forced to flee their homes, photographer Matt Inwood shares why he took The Ration Challenge.

By Matt inwood

18 june 2021

Could you live for a week eating the same ration pack as a Syrian refugee living in a Jordanian camp? This is the premise behind the innovative Ration Challenge, aimed at raising awareness and funds for people forced to leave their homes because of conflict or persecution. A quick look at those rations brings that question sharply into focus: just under 2kg of rice; 400g of flour; 170g of lentils; 85g of dried chickpeas; 120g of protein (sardines or tofu); 400g of kidney beans; and 330ml of vegetable oil. Right from the off, it really doesn’t sound like it will be nearly enough for a week, does it?

This is the second time I’ve tried it and naively when I took it last year I didn’t think it would be that tricky, and well worth it for such an important cause. When I asked myself the same question this year, it would be fair to say that last year’s experience had left its scar.

First off you’re sent a ration pack when you sign up: exactly the same box that’s distributed to refugees in the camps in Jordan. The box contains extra information about what you’re doing, who and how your donations will help, and a booklet with recipes for meal ideas.

Talking food

The question of what to eat, when and how much is one you need to address early. Planning is essential to ensure there’s some variety, however miserly that mix of ingredients might seem. I’ve worked in food publishing and food photography all my adult life, so I understand how to make meals, how to balance them and what the body requires in terms of energy and nutrition. The supplied portion of protein needs to stretch across a week, yet it’s conceivable that only last week you might have eaten that same quota in just one meal. Rice is the key food staple of more than half the people of this world, but when cooked without spice to flavour, and without protein or vegetable to bring taste, texture and balance, rice is a dish so bland that it offends from almost the very first day. It requires other elements to elevate it. Indeed, perhaps the cruelest aspect of a week of food rationing is that you finish with a surfeit of rice, because it begins to feel preferable to go hungry than to repeatedly eat the same tasteless thing. Rice bulks, but it won’t tame or temporarily mask hunger for long.

Bread was the food which brought the most pleasure. I carefully weighed and mixed flour with water and kneaded that into a soft dough and rolled it into discs. I fried these in a pan with a little vegetable oil and created the simplest flatbreads which I rationed throughout the week. Cooking each side a little longer than required causes a chemical reaction in the hot oil and colours the food – char, browning, blackening – and this brings a different and much valued dimension of flavour. The kidney beans and the precious juices they were sitting in were the ingredients I prized most. I added these several times to rice and I mashed them for a dip which was as flavourful as anything I ate all week.

I should confess that I made the Challenge harder for myself than I needed to. You are incentivised with ‘sponsorship rewards’ when you hit key fundraising milestones – salt, when you reach £75; 210ml of milk at £150; a tin of tomatoes at £600, and so on. These ‘rewards’ are aimed at making the experience more manageable and also replicate another part of the ‘authentic’ refugee camp experience, where people will openly trade with one another, swapping food for labour or goods in order to stretch or supplement their rations. I guess I wanted to experience the Challenge at its most basic premise: can you live off this box of ingredients for a week? I feared the possibility of making the parameters easier for myself would dilute the efficacy of the lessons of how we expect others in this world to survive.

How did I cope?

Looking back on the week, there are some very substantial physical and mental difficulties. From Day 1, deprivation is present in your mind. From Day 2, a lingering sense of hunger sets in and by the midweek point that hunger really does begin to feel very difficult to manage. I had to schedule the Challenge into a week that would see me working mostly from home (eating ambient temperature rice on the go is not really possible if you wish to avoid food poisoning on top of all the other difficulties), but even then I couldn’t avoid two incredibly long and arduous days of work, one in the middle and one right at the very end of my week. Work did, at least, bring a very welcome distraction, although the final day’s efforts left me feeling quite shattered and dehydrated.

Over the course of the week, my total calorie deficit was more than 11,500 calories. My total weight loss, from one Sunday morning to next Sunday morning weigh-in, was nine pounds. Total funds raised are just creeping up to the £1,000 goal I set for myself, compared with £3,750 raised last year. A global pandemic and the job losses, financial insecurities and money problems that have come with it make it difficult to ask others to donate – but so many did and I am extremely grateful to all of them, and to the many more who shared my Challenge with their friends and followers. Two other friends were inspired to start their own Challenges and are now completing their weeks having raised many, many hundreds of pounds each themselves.

Most importantly, the experience of the week helps to reinforce and add to what we know about the other humans we share this world with – what each of us needs to survive, to sustain, to have dignity, to thrive. Millions of refugees all over the world have been displaced from their homes, from their perfectly secure lives and livelihoods, their cultures, their families, their friends, their faiths: through no fault of their own. They rely on a cardboard box of meagre ingredients to survive. A week of living with only one of those aspects of qualitative life removed – food – was incredibly hard. And so I can’t imagine I won’t repeat the hardship next year and hope that others will be encouraged to try to walk in those same shoes too.

There are millions of good people – all of whom were once healthy, independent, self-sufficient, happy, innocent – who now depend on the charity of others due to circumstances utterly beyond their control. Seven days of feeling hungry should ensure that we each do better and work harder and be kinder towards others with each of the remaining 358 days of the year.

100% of profits from the sales of #TOGETHER products go to charities that advance the Sustainable Development Goals. Find out more here.